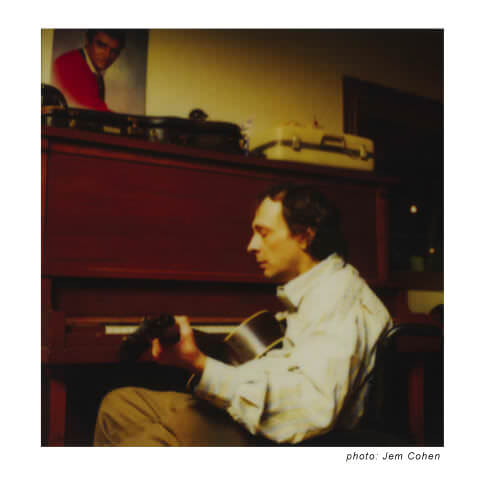

Vic Chesnutt - West of Rome

VIC CHESNUTT Nov. 12, 1964 - Dec. 25, 2009

Liner Notes: for the West of Rome album re-issue, 2004

I first met Vic by chance in 1987, late one night at an Athens Georgia coffee shop. I didn’t know he was a musician, but as soon as I heard Little, I became a dedicated admirer. In 1991, while helping filmmaker Peter Sillen with his documentary on Vic, I was around for the making of this record. When we arrived to shoot the session, Vic was in the hospital, a place to which he is no stranger. Pneumonia. He went straight into the studio the next day.

Recording and mixing took less than two weeks. Total. Vic had made demos of some of the songs on his home 4-track, but this record was a big step for him. Engineer Scott Stuckey’s studio was across from the kitchen in his house, on a long, tree-lined street. Scott had done a bit of engineering work with others, but West was the first full-length record he’d done on his own. He had just bought the used mixing board a week before the session.

Michael Stipe, who’d instigated the stripped down Little album, was to take a more active role as producer of this one. Stuckey had certainly never worked with Stipe, but they got right down to it. Michael was serious and concentrated. Maybe the session was something of an oasis. (R.E.M. had just gotten their first gold record and Scott remembers him having to take a long walk around the block about it). He didn’t have a cell phone. No one did. He also, luckily, wasn’t exactly a gearhead studio wiz, and that allowed him to focus more simply on the matter at hand; seeing these songs realized in an honest, unpasteurized way that still allowed Vic to stretch out. Producer Hal Wilner has said that it is one of the best-produced records ever, and I agree. It isn’t because it’s perfect (it might even be because it isn’t). It just sounds like it absolutely shouldn’t be any other way.

Listening to ‘Big Huge Valley’ or ‘Soggy Tongues’ you find yourself in a room with the players, a small room. The band rolls along, sometimes loping just slightly behind Vic in a way that is just right. If there were pieces of paper around Tina’s bass amp with chord progressions on them in big letters, it matters not a bit. Her playing is solid and true. It is just right. Jeffrey, the drummer, I had once seen kneeling on stage in the dark, “playing” Vic’s wheelchair which had somehow been rigged with contact microphones. It sounded incredible. Here again, his playing is simultaneously discreet and forceful. It is just right. The presence of Vic’s string-playing nieces is key to the session. At 14 and 16 years old, they looked like they’d been sprung from high school band practice. They were shy but there was much beneath the surface. Vic knew it, and he and Michael brought it out. Their playing is just right. Michael also wrote and picked out keyboard and string parts and Ray Neal, then in the extraordinary Miracle Legion, sat in on guitar and helped a little with the mix. Scott says that it is the most magical recording session he’s ever been involved with, but at the time I don’t think anyone was congratulating themselves about it. Why do things sometimes fall into place, and why are they sometimes left to lay as they’ve fallen, or just nudged a perfect touch to the right or left? In the title track, Vic’s backing vocal hovers just so in the air, like the things the man in the song can’t quite reach. When the main vocal cuts loose at the end, it’s a wordless string of syllables that has so much to do with great and terrible distances. Vic says “We had no idea what I was gonna do at that moment. I thought I was gonna just hum, and then when the moment came I just belted that out – I was a long way from the mic.”

Vic has certainly seen - and even instigated - some rough times, but one of the nice things about a reissue is that it affords a chance to look back and see the seeds of luck and good chance that continue to blossom today.

One of the small chance things that I’m happiest about in my life is that I sent Vic a postcard that helped inspire the song “Sponge.” It wasn’t anything I wrote that did it; it was the photograph on the card, taken by Helen Levitt in 1939. Three small children on an old New York City stoop. They wear crude masks and look out at us and the world in a way that is utterly unsentimental, beautiful, and possibly terrifying. A wild range of influences infiltrates Vic’s work as a whole. At the time of the West of Rome session, he had a sort of cardboard-and-Magic-Marker Pope’s hat that he wore, at least around the house, as a re-creation of the Francis Bacon paintings of the screaming Pope. Outside of Vic and Tina’s little house was their black Chevy van, crudely spray-painted with the word ‘Sophisticated’ in large pink letters. Inside the house, under a refrigerator magnet, I recall a photo of Vic’s grandfather, Sleepy, posing with his Country and Western band. Mixing all of these together, perhaps you can get a sense of where Vic was coming from. He also came, literally, from Florida, which he tragically and hilariously memorializes on the record. (On the same refrigerator you might also imagine a wedding picture of Vic and Tina, who had just been married a year when the record was made. No such picture exists, because there was no camera at the truckstop where they were married).

This re-release allows for two important returns to original intentions. ‘Latent Blatant’ no longer opens the record, and the misprinted lyrics of the title song are corrected from ‘steeped in the dark isolation’ to ‘steeped in those dark oscillations.’ It’s an important change, maybe because to me the former could be that of one man, while the latter touches on something else, reverberant and shared. The phrase makes me think of that underlying universal tone that physicists and philosophers look for, and of the Doppler Effect in the sound of a receding train.

And it also reminds me of the cello note, the ‘Low D,’ that anchors the song ‘Panic Pure.’

Everyone was leaving the studio one night, halfway out the door as I recall, when Vic announced that he wanted to try laying down the song’s vocal. The lights stayed out; a couple of candles were lit in the vocal booth. I think he nailed it in one take. It was like hearing dusk itself turn into sound, one of the most powerful moments I’ve had the privilege to witness. I always remember the song as sounding sadder than it actually does, with its easy wandering lilt and a drumbeat that is gentle and martial in equal measure, but it is strong stuff. My favorite song on one of my very favorite records ever.

What else can I say? If you ride the shuttle bus that goes around the rim of the Grand Canyon, you can hear the driver announce “Next stop, the Abyss…” which is just the name of a stop along the ridge. Somehow, Vic’s music echoes that for me; the sweetness of the little intercom, a trusted guide, and to your left, the yawning chasm. On the other hand, West of Rome is nothing like the Grand Canyon at all. It’s a very humble album, straight up and intimate, free of self-importance, mighty in spite of the humility with which it was made. It’s also full of humor, like much of Vic’s work.

The abyss exists. Vic is one who won’t let us pretend otherwise, and it sometimes makes him to howl. But it’s still a howl of celebration. Turn out the lights sometime when you listen to this record.

Jem Cohen, Winter 2004

footnotes:

1 Pope Innocent X, after Velasquez.